|

|

| (No se muestran 26 ediciones intermedias de 3 usuarios) |

| Línea 1: |

Línea 1: |

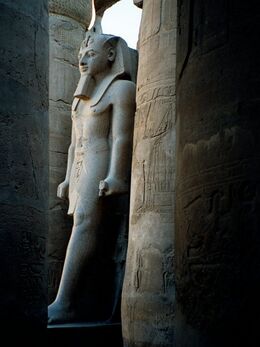

| [[Archivo:Egypt.LuxorTemple.02.jpg|right|thumb|260px|Estructuras que exceden con creces la duración de la vida de un ser humano perduran en [[Karnak]] 3400 años luego de su construcción]]

| | {{+}}<div style="float:right;"><hovergallery widths=260px heights=420px mode=nolines perrow=1>Egypt.LuxorTemple.02.jpg|{{AltC|Estructuras que exceden con creces la duración de la vida de un ser humano perduran en Karnak 3400 años luego de su construcción}}</hovergallery></div> |

| La '''arquitectura religiosa''' se ocupa del diseño y la construcción de los [[place of worship|sitios de culto]] y/o sagrados o espacios de oración, tales como [[Church architecture|iglesias]], [[mezquita|mezquitas]], [[stupa]]s, [[sinagoga]]s, y [[templo]]s. Muchas culturas han dedicado grandes cantidades de recursos a su arquitectura religiosa, y sus lugares de culto y espacios sagrados se encuentran entre las [[edificaciones]] más impresionantes y perdurables que ha creado la humanidad. Por dicha razón, la disciplina occidental de ''Historia de la Arquitectura'' sigue en buena medida la historia de la arquitectura religiosa desde las épocas más remotas hasta por lo menos el [[período Barroco]]. La [[geometría sacra]], la [[iconografía]] y el uso de sofisticadas [[semióticas]] tales como signos, símbolos y motivos religiosos son endémicos en la arquitectura religiosa. | | La '''arquitectura religiosa''' se ocupa del diseño y la construcción de los sitios de culto y/o sagrados o espacios de oración, tales como iglesias, [[mezquita]]s, Stupas, [[sinagoga]]s, y templos. Muchas culturas han dedicado grandes cantidades de recursos a su arquitectura religiosa, y sus lugares de culto y espacios sagrados se encuentran entre las Edificaciones más impresionantes y perdurables que ha creado la humanidad. Por dicha razón, la disciplina occidental de ''Historia de la Arquitectura'' sigue en buena medida la historia de la arquitectura religiosa desde las épocas más remotas hasta por lo menos el Período Barroco. La Geometría sacra, la iconografía y el uso de sofisticadas Semióticas tales como signos, símbolos y motivos religiosos son endémicos en la arquitectura religiosa. |

|

| |

|

| Las estructuras religiosas a menudo evolucionan durante períodos de varios siglos y eran las mayores construcciones del mundo, antes de la existencia de los modernos rascacielos. Mientras que los diversos estilos empleados en la arquitectura religiosa a veces reflejan tendencias de otras construcciones, estos estilos también se mantenían diferenciados de la arquitectura contemporanea utilizada etilizada en otras estructuras. Con el ascenso de las religiones monoteistas, los edificios religiosos se fueron convirtiendo en mayor medida en centros de oración y meditación. | | Las estructuras religiosas a menudo evolucionan durante períodos de varios siglos y eran las mayores construcciones del mundo, antes de la existencia de los modernos rascacielos. Mientras que los diversos estilos empleados en la arquitectura religiosa a veces reflejan tendencias de otras construcciones, estos estilos también se mantenían diferenciados de la arquitectura contemporanea utilizada etilizada en otras estructuras. Con el ascenso de las religiones monoteistas, los edificios religiosos se fueron convirtiendo en mayor medida en centros de oración y meditación. |

|

| |

|

| ==Aspectos espirituales de la arquitectura religiosa== | | ==Aspectos espirituales de la arquitectura religiosa== |

| A veces la arquitectura religiosa es llamada espacio sacro. El arquitecto Norman L. Koonce ha sugerido que el objetivo de la arquitectura religiosa es hacer "transparente la frontera entre la materia y la mente, la carne y el espíritu." Comentando sobre la arquitectura religiosa el mimistro protestante [[Robert Schuller]], ha sugerido que "para ser sano sicológicamente, los seres humanos necesitan experimentar su entorno natural—el entorno para el que fueron diseñados, que es el jardín." En tanto, Richard Kieckhefer sugiere que entrar en un edificio religioso es una metáfora de entrar en una relación espiritual. Kieckhefer sugiere que el espacio sacro puede ser analizado mediante tres factores que afectan el proceso espiritual: el espacio longitudinal enfatiza la procesión y regreso de los actos sacramentales, el espacio de auditorio es sugestivo de la proclamación y la respuesta, y las nuevas formas del espacio comunal diseñado para reunirse depende en una gran medida en una escala minimizada para lograr una atmósfera de intimidad y de participación en la oración. | | A veces la arquitectura religiosa es llamada espacio sacro. El arquitecto Norman L. Koonce ha sugerido que el objetivo de la arquitectura religiosa es hacer "transparente la frontera entre la materia y la mente, la carne y el espíritu." Comentando sobre la arquitectura religiosa el mimistro protestante Robert Schuller, ha sugerido que "para ser sano sicológicamente, los seres humanos necesitan experimentar su entorno natural—el entorno para el que fueron diseñados, que es el jardín." En tanto, Richard Kieckhefer sugiere que entrar en un edificio religioso es una metáfora de entrar en una relación espiritual. Kieckhefer sugiere que el espacio sacro puede ser analizado mediante tres factores que afectan el proceso espiritual: el espacio longitudinal enfatiza la procesión y regreso de los actos sacramentales, el espacio de auditorio es sugestivo de la proclamación y la respuesta, y las nuevas formas del espacio comunal diseñado para reunirse depende en una gran medida en una escala minimizada para lograr una atmósfera de intimidad y de participación en la oración. |

| <!--

| | {{Referencias}} |

| | |

| ==Ancient architecture==

| |

| [[Archivo:Karnak Temple Interior.jpg|right|thumb|right|Interior of [[Karnak|Karnak Temple]]]]

| |

| Religious architecture spans a number of ancient architectural styles including [[Neolithic architecture]], [[ancient Egyptian architecture]] and [[Sumerian architecture]]. Ancient religious buildings, particularly temples, were often viewed as the dwelling place of the gods and were used as the site of various kinds of sacrifice. Ancient tombs and burial structures are also examples of architectural structures reflecting religious beliefs of their various societies. The [[Temple of Karnak]] at Thebes, Egypt was constructed across a period of 1300 years and its numerous temples comprise what may be the largest religious structure ever built. Ancient Egyptian religious architecture has fascinated archaeologists and captured the public imagination for millennia.

| |

| | |

| ==Classical architecture==

| |

| {{see also|Classical architecture|Architecture of Ancient Greece|Roman architecture}} | |

| [[Archivo:ac.parthenon5.jpg|thumb|The Parthenon in Athens, Greece]]Around 600 B.C. the wooden columns of the Temple of Hera at Olympia were replaced by stone columns. With the spread of this process to other sanctuary structures a few stone buildings have survived through the ages. Greek architecture preceded Hellenistic and Roman periods (Roman architecture heavily copied Greek). Since temples are the only buildings which survive in numbers, most of our concept of classical architecture is based on religious structures. The [[Parthenon]] which served as a treasury building as well as a place for veneration of deity, is widely regarded as the greatest example of classical architecture.

| |

| ==Indian architecture==

| |

| {{see also|Indian rock-cut architecture|Hoysala architecture|Hindu temple architecture}}

| |

| [[Indian architecture]] is related to the history and religions of the time periods as well as to the geography and geology of the Indian subcontinent. India was crisscrossed by trading routes of merchants from as far away as [[Siraf]] and [[China]] as well as weathering invasions by foreigners, resulting in multiple influences of foreign elements on native styles. The diversity of Indian culture is represented in its architecture. Indian architecture comprises a blend of ancient and varied native traditions, with building types, forms and technologies from [[West Asia|West]], [[Central Asia]], and [[Europe]].

| |

| | |

| ===Buddhism===

| |

| {{seealso|Buddhist architecture}}

| |

| [[Archivo:Templeofthegoldenpavilion.jpg|*|thumb|[[Kinkaku-ji]], or Temple of the Golden Pavilion]] [[Buddhist architecture]] developed in [[South Asia]] beginning in the third century BC. Two types of structures are associated with early [[Buddhism]]: [[viharas]] and [[stupas]].

| |

| Originally, Viharas were temporary shelters used by wandering monks during the rainy season, but these structures later developed to accommodate the growing and increasingly formalized Buddhist [[monasticism]]. An existing example is at [[Nalanda]] ([[Bihar]]).

| |

| | |

| The initial function of the stupa was the veneration and safe-guarding of the relics of the [[Buddha]]. The earliest existing example of a stupa is in [[Sanchi]] ([[Madhya Pradesh]]). In accordance with changes in religious practice, stupas were gradually incorporated into [[chaitya]]-grihas (stupa halls). These reached their highpoint in the first century BC, exemplified by the cave complexes of [[Ajanta]] and [[Ellora]] ([[Maharashtra]]).

| |

| | |

| The [[pagoda]] is an evolution of the Indian stupa that is marked by a tiered [[tower]] with multiple [[eaves]] common in China, Japan, Korea, Nepal and other parts of Asia.

| |

| [[Buddhist temple]]s were developed rather later and outside South Asia, where Buddhism gradually declined from the early centuries AD onwards, though an early example is that of the Mahabodhi temple at [[Bodh Gaya]] in [[Bihar]]. The architectural structure of the stupa spread across Asia, taking on many diverse forms as details specific to different regions were incorporated into the overall design. It was spread to China and the Asian region by [[Araniko]], a [[Nepal]]i architect in the early 13th century for [[Kublai Khan]].

| |

| | |

| ===Hinduism===

| |

| {{Main|Hindu temple architecture}}

| |

| [[Archivo:Raghunath Temple Jammu.JPG|*|thumb|The Sikhara of the [[Raghunath Temple]] at [[Jammu]], [[India]] is built in the "Nagar" style of temple architecture.]]

| |

| [[Archivo:Brihadeshwara front right.jpg|thumb|right|Dravida Style Brihadeeswara Temple, Tanjavur]]

| |

| [[Hindu temple architecture]] is based on Sthapatya Veda and many other ancient religious texts like the Brihat Samhita, Vaastu shastra and Shilpa Shastras in accordance to the design principles and guidelines believed to have been laid by the divine architect [[Vishvakarma]]. It evolved over a period of more than 2000 years. The Hindu architecture conforms to strict religious models that incorporate elements of [[astronomy]] and [[sacred geometry]]. In Hindu belief, the [[temple]] represents the [[macrocosm]] of the universe as well as the [[microcosm]] of inner space. While the underlying form of Hindu temple architecture follows strict traditions, considerable variation occurs with the often intense decorative embellishments and ornamentation.

| |

| | |

| A basic [[Hindu]] [[temple]] consists of an inner sanctum, the ''[[garbhagriha]]'' or womb-chamber, a congregation hall, and possibly an antechamber and porch. The sanctum is crowned by a tower-like ''[[shikara]]''. The [[Hindu temple]] represents Mount Meru, the axis of the universe. There are strict rules which describe the themes and sculptures on the outer walls of the temple buildings.

| |

| | |

| The two primary styles that have developed are the [[Nagara]] style of Northern India and the [[Dravida]] style of Southern India. A prominent difference between the two styles are the elaborate gateways employed in the South. They are also easily distinguishable by the shape and decoration of their shikharas. The Nagara style is beehive shaped while the Dravida style is pyramid shaped.

| |

| | |

| ==Byzantine architecture==

| |

| {{seealso|byzantine architecture}}

| |

| [[Archivo:Aya sofya.jpg|thumb|*|[[Hagia Sophia]], the Church of [[Holy Wisdom]]]] [[Archivo:KariyeCamii-Aussenansicht.jpg|thumb|The 6th Century Kariye Camii located in Istanbul is now a mosque.]]

| |

| Byzantine architecture evolved from Roman architecture. Eventually, a style emerged incorporating Near East influences and the Greek cross plan for church design. In addition, brick replaced stone, classical order was less stirctly observed, mosaics replaced carved decoration, and complex domes were erected. One of the great breakthroughs in the history of Western architecture occurred when Justinian's architects invented a complex system providing for a smooth transition from a square plan of the church to a circular dome (or domes) by means of squinches or pendentives. The prime example of early Byzantine religious architecture is the [[Hagia Sophia]] in Istanbul.

| |

| | |

| ==Islam==

| |

| {{seealso|Islamic architecture}}

| |

| Byzantine architecture had a great influence on early Islamic architecture with its characteristic round arches, vaults and domes. Many forms of mosques have evolved in different regions of the [[Muslim world|Islamic world]]. Notable mosque types include the early [[Abbasid]] mosques, T-type mosques, and the central-dome mosques of Anatolia.

| |

| | |

| [[Archivo:Mosque of Cordoba Spain.jpg|thumb|right|Interior of the [[Mezquita]], a hypostyle mosque with columns arranged in grid pattern, in [[Córdoba, Spain|Córdoba]], [[Spain]]]]

| |

| The earliest styles in Islamic architecture produced ''Arab-plan'' or ''hypostyle'' mosques during the [[Umayyad Dynasty]]. These mosques follow a square or rectangular plan with enclosed courtyard and covered prayer hall. Most early hypostyle mosques had flat prayer hall roofs, which required numerous [[column]]s and [[support]]s.<ref name="Masdjid1"/> The [[Mezquita]] in [[Córdoba, Spain|Córdoba]], [[Spain]] was constructed as a hypostyle mosque supported by over 850 columns.<ref name="mit-handout">{{Cite web|url=http://web.mit.edu/4.614/www/handout02.html |accessdate=2006-04-09 |publisher=Massachusetts Institute of Technology |title=Religious Architecture and Islamic Cultures}}</ref> Arab-plan mosques continued under the [[Abbasid]] dynasty.

| |

| | |

| [[Archivo:Ani.mosque.jpg|The ruins of Menüçehr Camii near Kars, Turkey, believed to be the oldest [[Seljuq dynasty|Seljuk]] mosque in Anatolia.|thumb|left]]

| |

| The [[Ottoman Empire|Ottomans]] introduced ''central dome mosques'' in the 15th century that have a large dome centered over the prayer hall. In addition to having one large dome at the center, there are often smaller domes that exist off-center over the prayer hall or throughout the rest of the mosque, in areas where prayer is not performed.<ref name="mit-vocab">{{Cite web|url=http://ocw.mit.edu/OcwWeb/Architecture/4-614Religious-Architecture-and-Islamic-CulturesFall2002/LectureNotes/detail/vocab-islam.htm#islam6 |accessdate=2006-04-09 |title=Vocabulary of Islamic Architecture |publisher=Massachusetts Institute of Technology}}</ref> The [[Dome of the Rock]] mosque in Jerusalem is perhaps the best known example of a central dome mosque.

| |

| | |

| ''Iwan mosques'' are most notable for their domed chambers and ''[[iwan]]s'', which are vaulted spaces open out on one end. In ''iwan'' mosques, one or more iwans face a central courtyard that serves as the prayer hall. The style represents a borrowing from pre-Islamic Iranian architecture and has been used almost exclusively for mosques in [[Iran]]. Many ''iwan'' mosques are converted [[Zoroastrism|Zoroastrian]] fire temples where the courtyard was used to house the sacred fire.<ref name="Masdjid1"/> Today, iwan mosques are no longer built.<ref name="mit-vocab" /> The [[Shah Mosque]] in [[Isfahan (city)|Isfahan]], [[Iran]] is a classic example of an ''iwan'' mosque.

| |

| | |

| A common feature in mosques is the [[minaret]], the tall, slender tower that usually is situated at one of the corners of the mosque structure. The top of the minaret is always the highest point in mosques that have one, and often the highest point in the immediate area. The first mosques had no minarets, and even nowadays the most conservative Islamic movements, like [[Wahhabism|Wahhabis]], avoid building minarets, seeing them as ostentatious and unnecessary. The first minaret was constructed in 665 in [[Basra]] during the reign of the [[Umayyad]] [[caliph]] [[Muawiyah I]]. Muawiyah encouraged the construction of minarets, as they were supposed to bring mosques on par with [[Christianity|Christian]] [[church]]es with their [[bell tower]]s. Consequently, mosque architects borrowed the shape of the bell tower for their minarets, which were used for essentially the same purpose — calling the faithful to prayer.<ref name="Manara">{{Cite encyclopedia | last = Hillenbrand| first = R | editor = P.J. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, [[Clifford Edmund Bosworth|C.E. Bosworth]], E. van Donzel and W.P. Heinrichs | encyclopedia =[[Encyclopaedia of Islam]] Online| title = Manara, Manar | publisher = Brill Academic Publishers | id = ISSN}}</ref>

| |

| | |

| Domes have been a hallmark of [[Islamic architecture]] since the 7th century. As time progressed, the sizes of mosque domes grew, from occupying only a small part of the roof near the [[mihrab]] to encompassing all of the roof above the prayer hall. Although domes normally took on the shape of a hemisphere, the [[Mughal Empire|Mughals]] in India popularized onion-shaped domes in [[South Asia]] and [[Persia]].<ref>{{Cite book|title=Architecture of Mughal India |last=Asher |first=Catherine B. |date=1992-09-24 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |pages=256 |id=ISBN |chapter=Aurangzeb and the Islamization of the Mughal style}}</ref>

| |

| | |

| [[Archivo:Prayer-hall-turkey.jpg|*|thumb|The prayer hall, or musalla, in a [[Turkey|Turkish]] mosque, with a [[minbar]]]]

| |

| | |

| The prayer hall, also known as the musalla, has no furniture; chairs and pews are absent from the prayer hall.<ref name="unitulsa">{{Cite web|url=http://www.utulsa.edu/iss/Mosque/MosqueFAQ.html |accessdate=2006-04-09 |publisher=The University of Tulsa |title=Mosque FAQ}}</ref> Prayer halls contain no images of people, animals, and spiritual figures although they may be decorated with [[Arabic calligraphy]] and verses from the [[Qur'an]] on the walls.

| |

| | |

| Usually opposite the entrance to the prayer hall is the ''[[qibla]] wall'', which is the visually emphasized area inside the prayer hall. The ''qibla'' wall is normally set perpendicular to a line leading to [[Mecca]].<ref>{{Cite book|title=Writing Signs: Fatimid Public Text |date=1998-12-16 |last=Bierman |first=Irene A. |publisher=University of California Press |pages=150 |id=ISBN}}</ref> Congregants pray in rows parallel to the ''qibla'' wall and thus arrange themselves so they face Mecca. In the ''qibla'' wall, usually at its center, is the [[mihrab]], a niche or depression indicating the ''qibla'' wall. Usually the ''mihrab'' is not occupied by furniture either. Sometimes, especially during [[Friday prayer]]s, a raised [[minbar]] or pulpit is located to the side of the ''mihrab'' for a [[khatib]] or some other speaker to offer a sermon ([[khutbah]]). The mihrab serves as the location where the [[imam]] leads the five daily prayers on a regular basis.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.ioc.u-tokyo.ac.jp/~islamarc/WebPage1/htm_eng/index/keyword1_e.htm |accessdate=2006-04-09 |title=Terms 1: Mosque |publisher=University of Tokyo Institute of Oriental Culture}}</ref>

| |

| | |

| [[Archivo:Ablution area inside Eastern wall of Badshahi mosque.JPG|right|thumb|People washing before prayer at the [[Badshahi Masjid|Badshahi mosque]] in [[Lahore]], [[Pakistan]]]]

| |

| | |

| Mosques often have [[wudu|ablution]] fountains or other facilities for washing in their entryways or courtyards. However, worshippers at much smaller mosques often have to use restrooms to perform their ablutions. In traditional mosques, this function is often elaborated into a freestanding building in the center of a courtyard.<ref name="mit-handout">{{Cite web|url=http://web.mit.edu/4.614/www/handout02.html |accessdate=2006-04-09 |publisher=Massachusetts Institute of Technology |title=Religious Architecture and Islamic Cultures}}</ref> Modern mosques may have a variety of amenities available to their congregants and the community, such as [[clinic|health clinics]], [[library|libraries]] and [[gym]]nasiums.

| |

| | |

| ==Medieval architecture==

| |

| [[Archivo:Urnesstavkirke.jpg|*|thumb|Norwegian stave church]]

| |

| {{seealso|medieval architecture}}

| |

| The religious architecture of Christian churches in the Middle Ages featured the [[Latin cross]] plan, which takes the Roman [[Basilica]] as its primary model with subsequent developments. It consists of a [[nave]], [[transept]]s, and the altar stands at the east end (see ''[[Cathedral diagram]]''). Also, [[cathedral]]s influenced or commissioned by [[Justinian I|Justinian]] employed the [[Byzantine architecture|Byzantine style]] of domes and a [[Greek cross]] (resembling a plus sign), centering attention on the altar at the ''center'' of the church. The [[Church of the Intercession on the Nerl]] is an excellent example of Russian orthodox architecture in the Middle Ages. The [[Urnes stave church]] (Urnes stavkyrkje) in [[Norway]] is a superb example of a medieval stave church.

| |

| | |

| ==Gothic architecture==

| |

| [[Archivo:Chartres 1.jpg|thumb|right|Cathedral of Chartres]]

| |

| {{seealso|Gothic architecture}}

| |

| [[Gothic architecture]] was particularly associated with cathedrals and other churches, which flourished in Europe during the high and late medieval period. Beginning in 12th century France, it was known as "the French Style" during the period. The style originated at the [[Saint Denis Basilica|abbey church of Saint-Denis]] in [[Saint-Denis]], near [[Paris]]. Other notable gothic religious structures include [[Notre Dame de Paris]], the [[Abbey Church of St Denis]], and the [[Chartres Cathedral]].

| |

| | |

| ==Renaissance architecture==

| |

| [[Archivo:Petersdom von Engelsburg gesehen.jpg|thumb|*|The Basilica of Saint Peter, Rome]]

| |

| {{seealso|Renaissance architecture}}

| |

| The Renaissance brought a return of classical influence and a new emphasis on rational clarity. Renaissance architecture represents a conscious revival of Roman Architecture with its symmetry, mathematical proportions, and geometric order. [[Filippo Brunelleschi]]'s plan for the [[Santa Maria del Fiore]] as the dome of the Florence Cathedral in 1418 was one of the first important religious architectural designs of the Italian renaissance.

| |

| | |

| ==Baroque architecture==

| |

| [[Archivo:Santa Susanna (Rome) - facade.jpg|thumb|right|Baroque façade of Santa Susanna, by [[Carlo Maderno]]]]

| |

| {{seealso|baroque architecture}}

| |

| (1603).]]Evolving from the renaissance style, the [[baroque]] style was most notably experienced in religious art and architecture. Most architectural historians regard [[Michelangelo]]'s design of [[St. Peter's Basilica]] in [[Rome]] as a precursor to the Baroque style. Baroque style can be recognized by broader inerior spaces (replacing long narrow naves), more playful attention to light and shadow, extensive ornamentation, large frescoes, focus on interior art, and frequently, a dramatic central exterior projection. The most important early example of the baroque period was the [[Santa Susanna]] by [[Carlo Maderno]]. [[Saint Paul's Cathedral]] in [[London]] by [[Christopher Wren]] is regarded as the prime example of the rather late influence of the Baroque style in England.

| |

| | |

| ==Latter-day Saint temples==

| |

| [[Archivo:Temple Square October 05 (8) c.JPG|thumb|*|[[Salt Lake Temple]]]]

| |

| {{Main|Temple architecture (Latter-day Saints)}}

| |

| [[Temple (Latter Day Saints)|Temples]] of [[The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints]] offer a unique look at design as it has changed from the simple church like structure of the [[Kirtland Temple]] built in their 1830s, to the [[castellated]] [[Gothic Revival architecture|Gothic]] styles of the early [[Utah]] temples, to the dozens of mass produced modern temples built today. The church has a total of 124 [[List of temples of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints|operating temples]] world wide, each with the same purpose. With the exception of the Kirtland Temple (no longer owned by the church), each has a Celestial room, one or more [[ordinance room]]s, and a baptistry with a font patterned after the description found in 1 Kings 7:23-25:

| |

| | |

| <blockquote>

| |

| "And he made a molten sea, ten cubits from the one brim to the other: it was round all about, and his height was five cubits: and a line of thirty cubits did compass it round about. And under the brim of it round about there were knops compassing it, ten in a cubit, compassing the sea round about: the knops were cast in two rows, when it was cast. It stood upon twelve oxen, three looking toward the north, and three looking toward the west, and three looking toward the south, and three looking toward the east: and the sea was set above upon them, and all their hinder parts were inward."

| |

| </blockquote>

| |

| | |

| Early temples, and some modern temples, have a priesthood assembly room with two sets of pulpits at each end of the room, with chairs or benches that can be altered to face either way. Most, but not all temples have the recognizable statue of the angel [[Moroni]] atop a spire. The [[Nauvoo Temple]] and the [[Salt Lake Temple]] are adorned with symbolic stonework, representing various aspects of the faith.

| |

| | |

| ==Modern and post-modern architectures==

| |

| [[Archivo:IndependenceTemple2.jpg|thumb|*|Community of Christ Temple in Independence, Missouri, USA is postmodern in design.]]

| |

| {{seealso|Modern architecture|Postmodern architecture}}

| |

| [[Modern architecture]] spans several styles with similar characteristics resulting in simplification of form and the elimination of ornament. While secular structures clearly had the greater influence on the development of modern architecture, several excellent examples of modern architecture can be found in religious buildings of the 20th century. For example, [[Unity Temple]] in Chicago is a [[Unitarian Universalist]] congregation designed by [[Frank Lloyd Wright]]. The Chapel of the [[United States Air Force Academy]] started in 1954 and completed in 1962, was designed by [[Walter Netsch]] and is an excellent example of modern religious architecture. It has been described as a "phalanx of fighters" turned on their tails and pointing heavenward. In 1967, Architect [[Pietro Belluschi]] designed the strikingly modern [[Cathedral of St. Mary of the Assumption]] (San Francisco), the first Catholic cathedral in the United States intended to conform to [[Vatican II]]. Post-modern architecture may be described by unapologetically diverse aesthetics where styles collide, form exists for its own sake, and new ways of viewing familiar styles and space abound. [[Independence Temple|The Temple]] at Independence, Missouri was conceived by Japanese architect [[Gyo Obata]] after the concept of the chambered nautilus. The Catholic [[Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels]] (Los Angeles) was designed in 1998 by [[Jose Rafael Moneo]] in a post-modern style. The structure evokes the area's Hispanic heritage through the use of adobe coloring while combining stark modern form with some traditional elements.

| |

| -->

| |

| ==Véase también==

| |

| *[[Place of worship]]

| |

| *[[Templo]]

| |

| *[[Capilla]]

| |

| *[[Catedral]]

| |

| *[[Sinagoga]]

| |

| *[[Ġgantija]]

| |

| *[[Karnak]]

| |

| *[[Mandir]]

| |

| *[[Mezquita]]

| |

| | |

| ===Notas===

| |

| <div class="references-small"><references/></div>

| |

| | |

| ===Referencias===

| |

| <div class="references-small"> | | <div class="references-small"> |

| *Jeanne Halgren Kilde, ''When Church Became Theatre: The Transformation of Evangelical Church Architecture and Worship in Nineteenth-Century America.'' (Oxford University Press:2002). ISBN | | *Jeanne Halgren Kilde, ''When Church Became Theatre: The Transformation of Evangelical Church Architecture and Worship in Nineteenth-Century America.'' (Oxford University Press:2002). ISBN |

| Línea 130: |

Línea 16: |

| </div> | | </div> |

|

| |

|

| ==Enlaces externos==

| |

| * [http://www.religiousarchitecture.org/ Arquitectura religiosa.org]

| |

| * [http://www.aia.org/ifraa_default Foro multiculto de religión, arte y arquitectura] American Institute of Architects

| |

| * [http://www.churchdevelopment.com/plans.html/ Ejemplos de diseño de iglesias contemporaneas]

| |

|

| |

| [[Categoría:Arquitectura religiosa]]

| |

| {{W}} | | {{W}} |

| | [[Carpeta:Arquitectura religiosa]] |